Isotope geochemistry is my primary tool, but I like to take interdisciplinary approaches to questions of environmental change and mass extinction.

My current research focus is repurposing clumped isotope geochemistry to learn about the physiology of both modern and extinct bivalve groups. I ultimately want to understand how shell formation strategies changed and diversified through time, and what all of this has to do with success in the ecosystem.

Read more about the paleoclimate, paleobiology, and the field/collections based aspects of my work below!

Paleoclimate

Understanding climate change through the millennia gives us insight into what makes Earth’s dynamic climate system tick. I am especially interested in past greenhouse worlds that can be used as analogs for future global warming.

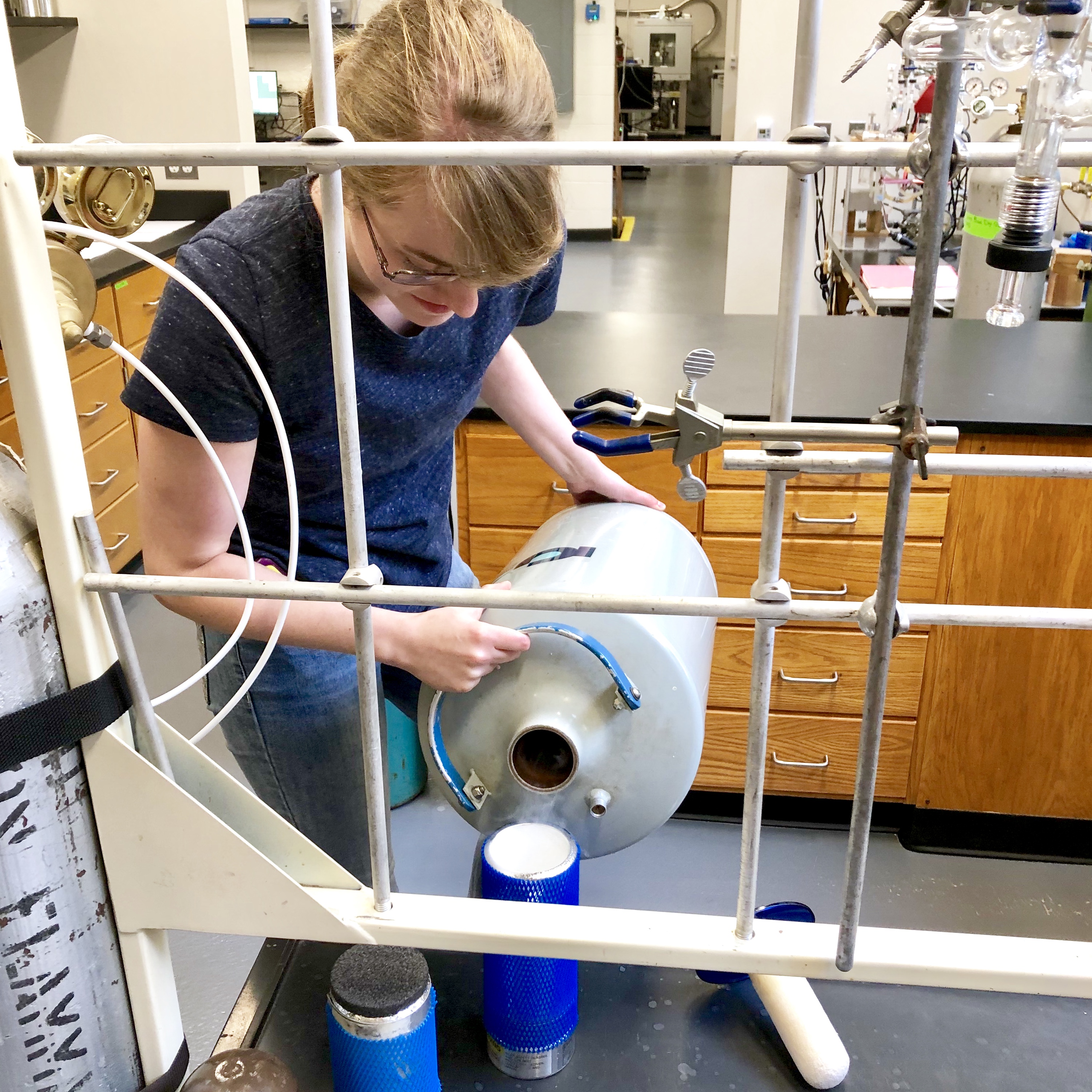

My main paleoclimatological tool is clumped isotope geochemistry. This provides empirical paleotemperature estimates based on the thermodynamics of bonding between multiple “heavy” isotopes of carbon and oxygen in a carbonate. With this temperature estimate, we can also reconstruct the isotopic composition of water bodies, which contains a lot of information about salinity, circulation, water cycling, and topography. I like to stay on the cutting edge of our paleoclimate methods, so I’m starting to incorporate dual clumped isotope analysis in my work.

The precision work of high-resolution sampling (both for clumped isotopes and bulk stable isotopes) is an exciting way to get at paleoseasonality and animal life cycles. A big question on everyone’s minds is how the modern biosphere is going to react to continued global warming, especially in a “worst case” scenario. Reconstructing paleoclimate variability on a fine scale gives a fuller picture of what kinds of extremes are possible. Furthermore, coeval changes in the fossil record can inform what kinds of threshold conditions various species can tolerate.

Paleobiology

Beyond reconstructing climatic variables, I want to learn how marine life adapted to life in warmer worlds. Focusing on transitional periods like the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary allows me to assess what factors correlate with survivorship in the face of great change.

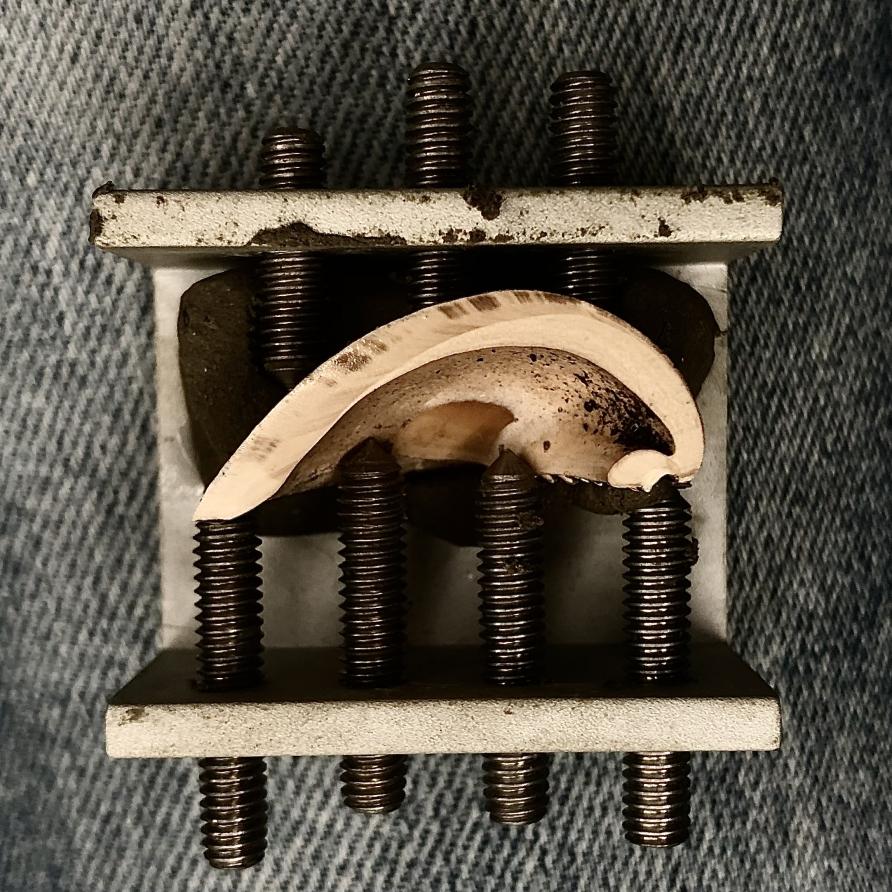

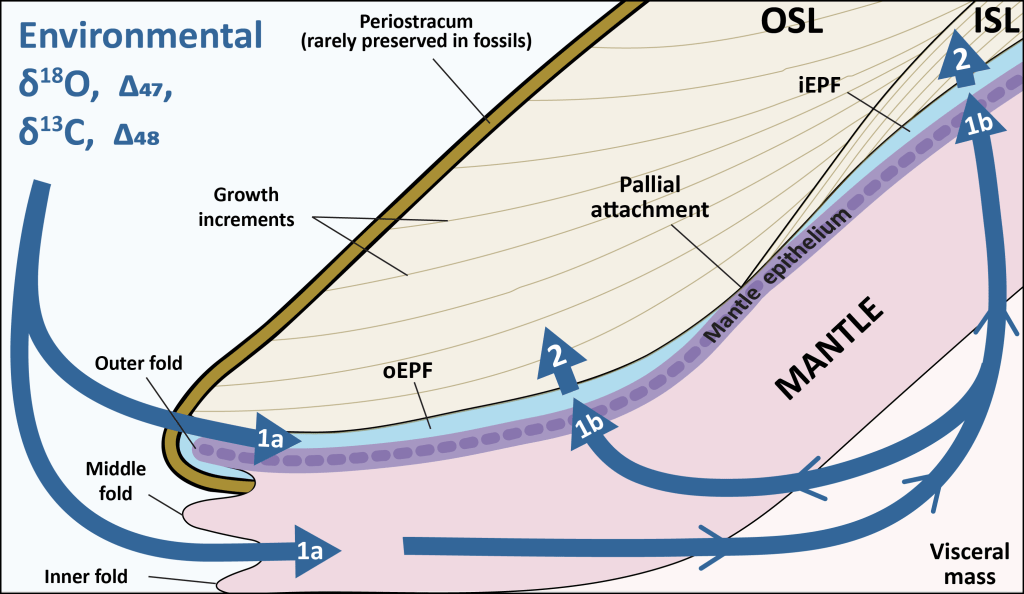

I am developing new methods and theory to identify “biologically driven isotopic fractionations” (BioDIFs), which preserve otherwise inaccessible aspects of bivalve physiology for millions of years. In February 2023, I published a synthetic review explaining the links we have found thus far between isotope geochemistry and biomineralization in fossil bivalves. This is a newly emerging field and there is still everything to learn!

Historically, geochemists have avoided sampling shells whose isotopic composition has been determined by anything other than water chemistry. Now, I’m deliberately seeking out these biological effects so that I can start to unravel the physiological story archived in the shell. What are the fractionating mechanisms, and when do fractionations occur during shell formation? How diverse actually are BioDIFs among bivalves, and how do they vary across the family tree? Why does preliminary work show that species with quite large physiological effects achieve better outcomes?

These are complex questions, and I have to throw a whole suite of methods at them to get a holistic picture: Dual clumped isotopes, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, morphometrics, and more.

Fieldwork & Collections

The fossil record is a non-renewable resource, so I leap at the change to make good use of existing natural history collections. However, archival records are imperfect and the contextual information you can get from in situ collection can be invaluable to reconstructing a bigger picture. Both are useful!

I’ve had a wide variety of field experiences throughout my career: from scrambling along scree slopes in Arizona to reach turquoise deposits, to measuring section and collecting fossils from quarries, to several weeks off grid mapping glaciers in the High Arctic. I’ve worked on samples from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology, the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, and in 2023 was a resident predoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

As a discipline, the Earth sciences need to reckon with a history of colonialism and white supremacy that affects our fieldwork and archival work. During these field experiences, my collaborators and I took steps to engage local communities. My undergraduate work in the Southwest built on a preexisting relationship between my mentors and local Native American communities. Some historical information contextualizing my Arctic fieldwork was provided by the Nunavut Archives Program, and we in turn shared our results with them. This is an area where I can continue to learn, and I know that there are always better efforts to be made.